“Someone came—knocking at the door of a friend and beloved.

She asked, ‘Who are you, O faithful man of honor?’

When he answered, ‘It is I,’ she replied, ‘Begone—this is not the time;

there is no place at this table for one who remains unripe.

What else can the unripe be refined by, if not the fire of separation?

What else can save him from hypocrisy?’

That poor wretch departed; for a full year he roamed the roads,

blazing with the sparks of his beloved’s absence,

burning fiercely.

The one who had been scorched emerged tempered, ripened.

He returned, again lingering near his beloved’s house.

With a hundred fears and a hundred mindful acts of decorum,

he knocked on the door’s ring—terrified that an unseemly word

might slip from his lips.

She cried, ‘Who stands there at the door?’

He said, ‘O captor of hearts—it is you who stands there at the door.’

She answered, ‘Then come in, since you are I.’

But the house is narrow—there is simply no room for two.”

(Masnavi, Book 1, vv. 3068–3075) — The Consciousness of Deli Dumrul (Crazy Dumrul)

Mr. Bilgin SAYDAM,

We are living in a time when we must reflect at length upon “ourselves.” Who are we, where do we come from, where are we going? What is our place within the family of humankind and in history? Indeed, does there truly exist such a thing as a “We”?

Your book, The Consciousness of Deli Dumrul (Crazy Dumrul), to which you have given the subtitle An Attempt at a Cultural Psychology of the Turkish–Islamic Spirit—and which is indeed the first and an original example of its kind—is a resource to which one can turn when pondering these questions.

You state that “the analysis of memory as the sediment of experiences, the transformation of the unknown into the knowable, is, as T. Kuhn puts it, ‘a paradigmatic leap.’” In this context, “mythology, as the psychology of ancient times, can be rendered knowable and poured into consciousness through the methods of psychology, which is the mythology of modern times.” As the great masters of psychoanalysis say, if myths are the collective dreams/fantasies of peoples, then by deciphering mythological tales we can reach profound insights into consciousness.

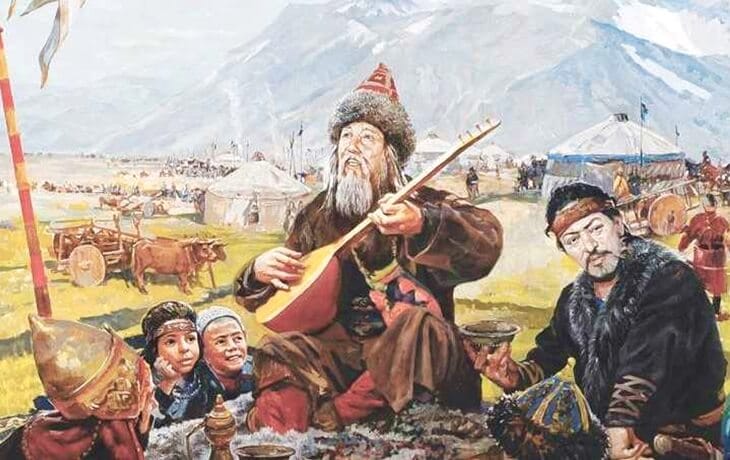

One of the most important stories in the Kitab-ı Dedem Korkut—one of the main sources of Turkish culture, consisting of tales dating to the 7th–11th centuries recounting the adventures of the Oghuz tribes—is The Tale of Duha Koca’s Son Deli Dumrul. When this story is analyzed using the methods of psychomythology, intriguing results have emerged.

You state that the reason you chose this story, Mr. Saydam, is that, in addition to fundamental existential themes such as death, mortality, and God, it offers direct information about the Islamization process of the nomadic Turkish culture rooted in shamanistic–animistic traditions, as well as about the formation of the contemporary Turkish–Islamic spirit. From this information, we gain important clues as to how the Islamization phase—the most significant transformation process in Turkish history—was experienced and how this profound change came about. In this way, we can establish, in the language of psychoanalysis, a suitable framework for considering what a behavioral pattern belonging to the “childhood” stage of the Turks means today, and the reasons behind it.

Let us first recall the story that most of us will remember from our schoolbooks:

The events take place in the Caucasus–Eastern Anatolia region, where the Oghuz tribes lived, probably sometime between the 9th and 11th centuries. A spirited young warrior named Deli Dumrul (Crazy Dumrul) had built a bridge over a dried-up stream, and he would demand 33 akçe (silver coins) from those who crossed it, and 40 from those who refused—beating them mercilessly in the process.

One day, cries and laments were heard from a nearby encampment: a “noble warrior” had died, and the entire community was plunged into mourning. Deli Dumrul wished to avenge the young man and learned that the one who had taken his life was Azrael. Mounting his horse, Dumrul set out in pursuit, caught up with Azrael, and fought him. Azrael escaped from the grasp of this “mad fool” and went to the Almighty God to explain the situation.

Deli Dumrul’s defiance of the divine will displeased God, who commanded Azrael to take Dumrul’s life. This time Azrael appeared before him in his majestic and terrifying form, subdued him, and said, “I have come to take your life by God’s command.” Deli Dumrul was seized with fear and, submitting to God, began to beg for his life to be spared. God was pleased and said to Dumrul, “If you can find a life in exchange for yours, I will pardon you.”

Deli Dumrul went first to his father, then to his mother, told them of his plight, and asked them to give their lives for him. Both refused, saying, “The world is sweet, life is dear,” and sent him away. At last, Dumrul’s wife—though she was “another man’s daughter” (el kızı)—said, “My life is a sacrifice for you,” and agreed to give her life.

However, when Azrael came to take her life, Dumrul pleaded with God, saying, “Either forgive us both, or take both our lives.” God showed mercy, pardoned Deli Dumrul and his wife, granted each of them 140 more years of life, and took instead the lives of Dumrul’s aged parents.

Mr. Saydam, in your analysis of this story through the method of psychoanalysis—your field of expertise—you primarily proceed from the examination of the masculine and feminine principles. In the person of Deli Dumrul, the “narcissistic inflation” that emerges, the rejection of the mother–father, and the death representing the “first self” as the feminine principle/maternal action, along with the transition to the masculine principle/paternal action—represented by Islam as the idea of the One God—form the foundations of your psychomythological analysis.

It should be emphasized that the characteristics belonging to this masculine–feminine dichotomy are not specific to gender; rather, they are common principles found in both sexes at the level of humanity.

Mother/nature—that is, the feminine principle—reflects the motif of seeking the positively experienced qualities of the mother and of nature. The expectations a child has of the mother—protection, sheltering, carrying, shielding, wrapping, warming, feeding, soothing, lulling to sleep—are described as maternal action. Motherliness (anacılık) is the effort to retreat into the mother’s embrace in order to relieve the pain that emerges as individuals grow more conscious, sacrificing the gains of consciousness to do so. This need surfaces in every human being throughout life, as the child within us.

The child grows toward becoming an adult who seeks, questions, discovers, acts, and takes initiative. Thus, the “mother’s embrace” now takes on a function that constricts, swallows, imprisons, dissolves, pushes back into the womb, and infantilizes—and the escape from the mother begins. This is the act of anakaç (“flight from the mother”): the act of fleeing from or distancing oneself from the unconscious (childhood) that extinguishes consciousness.

The masculine principle is the formation of consciousness and its acquisition of a distinguishing, analytical, defining, and commanding quality. Paternal action involves movement toward assimilating the logos (rule) and nomos (law) carried and offered to its members by the community in which the individual lives. Masculinity is the attractive element of individuation. For the child-consciousness that becomes an individual by separating from the mother–child dyad, this element is concretized in the “father.”

You say, “Throughout human history, the formation of consciousness and the development of cultures have been made possible through paternalism and anakaç (flight from the mother) action. Every human being and every culture necessarily passes through a maternalist phase. However, dominant maternalism hinders the grasping and use of nature as a tool, technological development, the transition to a settled order and the subjugation of the environment, and the formation of enduring urban cultures.

The separation of human beings from nature (the mother) and their attainment of self-consciousness—their differentiation from all other creatures—is an evolution from the unconscious to consciousness, from nature to spirit, from the feminine principle to the masculine principle.”

This conceptual framework also enables us to explain the developmental journey of humanity. Hunter–gatherer communities, subject to nature and the feminine principle, represent the stage of the “thing-human” (Man), who has not yet attained self-awareness or a sense of humanity.

The transition to a settled order requires agriculture, technology, and organization, and the creative–active agency that makes this possible is the product of the masculine principle/spirituality.

While still in the stage of maternalist action in terms of mentality and way of life, the animistic–shamanistic nomadic Turkish tribes encountered Islam, which represented a paternalist belief system and way of life. In your words, “The paternalist philosophy of life brought with it a departure from the feminine principle, from dependence on nature, and from blood and kinship ties; it fostered autonomy and individualization. The individual identity shaped by the faith and worship required by being solely responsible before Allah replaced the identity of the family or tribe. For the animist Turk, who lived in intimate union with nature and maintained a direct relationship with the sacred, to grasp the concept of ‘Allah’—with its absoluteness, indescribability, and uniqueness—was a very advanced step, a qualitative leap.”

If we move from this theoretical framework to the story itself: the Oghuz tribes are undergoing a process of Islamization. The Islamization of these nomadic communities, who encountered the Arab–Islamic armies, took place under “compulsion” and with considerable difficulty. The Turkish tribes submitted to the adherents of this new religion, who were stronger than them in both the level of civilization and mentality. They were forced to abandon their past and their ancestral culture. However, this great transformation breathed new life into the Turkish tribes, who—while in the course of migration—were facing the threat of extinction and erasure from history as they became absorbed into new cultures, and their journey through history continued, gaining a higher quality parallel to their geographical journey.

Deli Dumrul built a bridge—a means of livelihood—over a dried-up stream, that is, over a community whose means of survival had vanished, who roamed continually in search of homelands in which they could live, and in doing so established a kind of tyrannical leadership–state. Logos (rule) and nomos (law) were his. However, after being defeated by the ever-advancing Arab armies (Azrael), they submitted to “the stronger one,” Islam. They encountered the one and only almighty (glorious) God. His authority was accepted, and in exchange for abandoning—dying to—the past (the aged mother and father), a new and longer life (the Turkish–Islamic spirit) was gained. The critical role was played by “the daughter of another” (el kızı)—that is, the Muslim communities—who, by entering into good relations and trade with the animist–shamanist Turks, opened the door to a new life, a new family, and a new way of living.

To summarize:

- The Turks were compelled to accept Islam because they understood that it was stronger and that it would add to their own strength.

- This process of acceptance took place by breaking away from the past and sacrificing the cult of the ancestors.

- In adapting to the new, the mercy of God—“the Merciful and the Compassionate”—that is, the Sufi interpretation of Islam, which was not alien to the old Turkish and Asian beliefs, played a major role, and the Turks found the opportunity to preserve some of their traditions within Islam.

You state that the characteristics of the Turkish spirit’s transition from the feminine principle/nature (animist–shamanist nomadic identity) to the masculine principle/spirituality (settled order and a monotheistic, rational mentality) contain many clues for understanding both the solutions that exist today and the unresolved problems we have yet to overcome. It is impossible not to disagree.

First of all, we can find direct parallels between the attitude we have developed since the 18th century (shall we call it the Vienna defeat?) when faced with a new development—Western modernity—that is stronger than us, and Deli Dumrul’s stance toward Azrael–God. Even today, we can see parallels between the attitude of those who adopt the tendency to forget or abandon our past, religion, and identity, and Dumrul’s invitation to have his own parents killed in his place. Indeed, the similarity between our 200-year-long effort and insistence on Westernization and the way we entered Islam 1,000 years ago—both in terms of submission to power—is quite striking. Could the tendency, as we Westernize, to force the “old” (Islamic culture) into a harmless subculture be a remnant of the attitude toward shamanism after the transition to Islam?

I ask you, Mr. Saydam—could Deli Dumrul be not merely a simple story, but the mythological distillation of our destiny? Or is it a “we-person” that sometimes manifests as the “State,” sometimes as a mirror reflecting the average of all of us, and that repeats itself as one of our social archetypes?

Would it be an exaggeration to say that our immutable psychology—whether in our individual identities and behaviors or as a society and a state—can be summarized as narcissistic inflation, submission to power, striving to resemble power, sacrificing the old for the new, accepting the new without fully understanding it, and even volunteering to serve it? To me, even the fact that our relationship with the West conforms to this sequence is, as a matter of honor, reason enough to question its course.

Thanks to Islam, we have now “grown up”—that is, we have attained self-awareness, established settled orders, and produced highly advanced examples of paternal action. Therefore, we must think and act like a mature and healthy community. When did we lose our capacity to develop healthier attitudes? How did we forget our sense of direction, our knowledge of the way, our spiritual and moral faculties? Why have so many of our people turned into worms that worship everything “high up”? Why has our “generous and just” state come to resemble Deli Dumrul, who hands out an extra 33 akçe to those who flatter every new policy and beats dissenters while taking 40 from them? Why are our children multiplying into passive, maladaptive, aimless, unhappy personalities—that is, regressing toward maternalist behavior?

And yet, we long ago ceased to be the Deli Dumrul type. Over the past thousand years, we have accumulated vast experience. We have fought, won, and lost. We have founded states and ruled empires. We have rejoiced and suffered. We have lived through everything a human being—or a society—can live through. So why, Mr. Saydam, are we still behaving like a spastic child?

Why can we not develop creative leaps, qualitative transformations, healthy and conscious reflexes? When, and how, will we muster the courage to change this fate?

I began by saying that we need to think and speak at length about ourselves. As I conclude my letter, I say this: beginning with the state and our esteemed statesmen, let us, as a whole country, put our hats on the table, set aside these “you and I” divisions, and—rich and poor, learned and unlearned, Turk and Kurd, Caucasian and Balkan alike—try to think and speak thoroughly about ourselves as “We.” Let us, without Articles 159, 312, and 146 and the like—without censorship, without limits—lay everything on the table.

If we were to sustain this for several years, and, with the taste of being a nation and the wisdom of being a state, achieve syntheses and consensuses that surpass the reflexes and boundaries of Deli Dumrul, we could plan our future together and rebuild the entire political and economic order.

In other words, I am suggesting that we do something normal, ordinary, human: to construct a civilized sense of self in which maternalist action has been transcended at the masculine level.

In short, let us, for the first time, carry out our historical journey, our existence and survival, and our demands for freedom and justice—not at the mercy of external dynamics, but as ourselves, willingly and joyfully.

I wonder, as a psychiatrist, would you consider this dream of mine too narcissistic, Mr. Saydam? Tell me, have we really come to such an end—are we so utterly spent?

Farewell.

The Consciousness of Deli Dumrul (Crazy Dumrul), M. Bilgin Saydam, Metis Publishing, Istanbul, 1997